In the annals of human history, there are tales of journeys that have driven men to the brink

of madness, and beyond. Such is the one that I am about to recount, a voyage that took me to the

furthest corners of bundle open, and binding.break. It is a journey that defies explanation,

and yet I cannot deny its reality. The metaprogamming that I witnessed, the unspeakable layers of

abstraction that I encountered, have left me forever scarred, and driven me to the very brink of sanity.

And yet, I must tell this story, for the world must know of the darkness that lies beyond the veil of

our static site generators, waiting to consume us all.

A nice little coding project

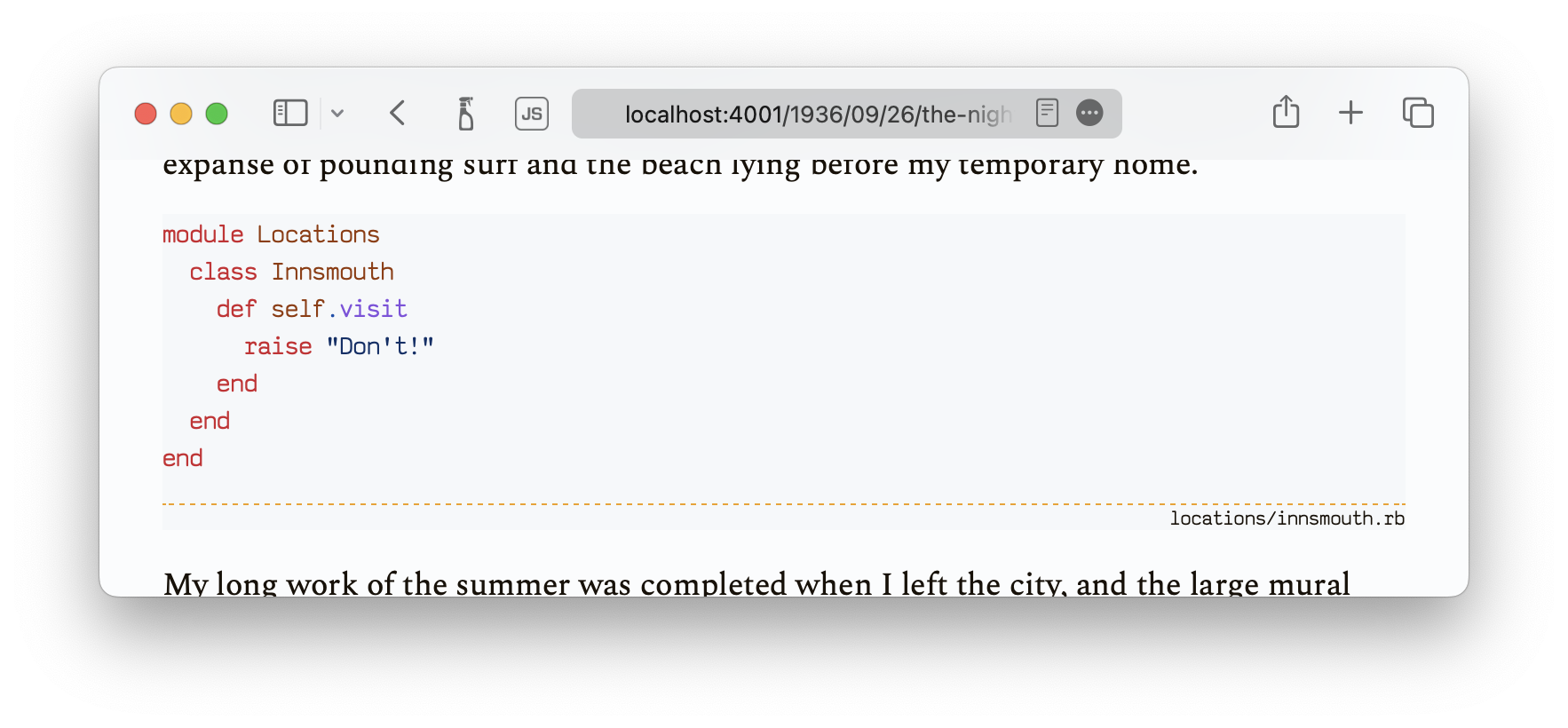

So, here’s the thing. I am currently writing a series of tutorials with a lot of code excerpts, taken from several different files. To make the context of each code sample obvious, I’ve been starting each code block with a comment indicating the name of the relevant file, like so:

# locations/innsmouth.rb

module Locations

class Innsmouth

def self.visit

raise "Don't!"

end

end

end

This works well, but frustrates my obsession with semantic HTML. The name of the file is not really

part of the code sample; it is rather its caption. And there are HTML elements for such things: <caption>

for adding captions to tables, and <figcaption> to add them to, well, any other content.

By default, Jekyll renders fenced code blocks with

a <pre> and a <code> elements, wrapped in two <div>’s:

<div class="language-ruby highlighter-rouge">

<div class="highlight">

<pre class="highlight">

<code>

…

</code>

</pre>

</div>

</div>

The <div>’s are a bit redundant, but fine; what I wanted was for either them or the <pre> element to be wrapped in a

<figure>, alongside a <figcaption>. For example, having Jekyll generate this would have been great:

<div class="language-ruby highlighter-rouge">

<div class="highlight">

<figure>

<pre>

<code>

…

</code>

</pre>

<figcaption>locations/innsmouth.rb</figcaption>

</figure>

</div>

</div>

Jekyll is said to be easy to extend, so what could be hard in writing some kind of plugin to enhance the rendering of fenced code blocks? On a fateful whim, I decided to embark on this journey…

Preparations

I gathered my supplies and made the necessary arrangements, all the while feeling an ominous dread lurking within my very soul.

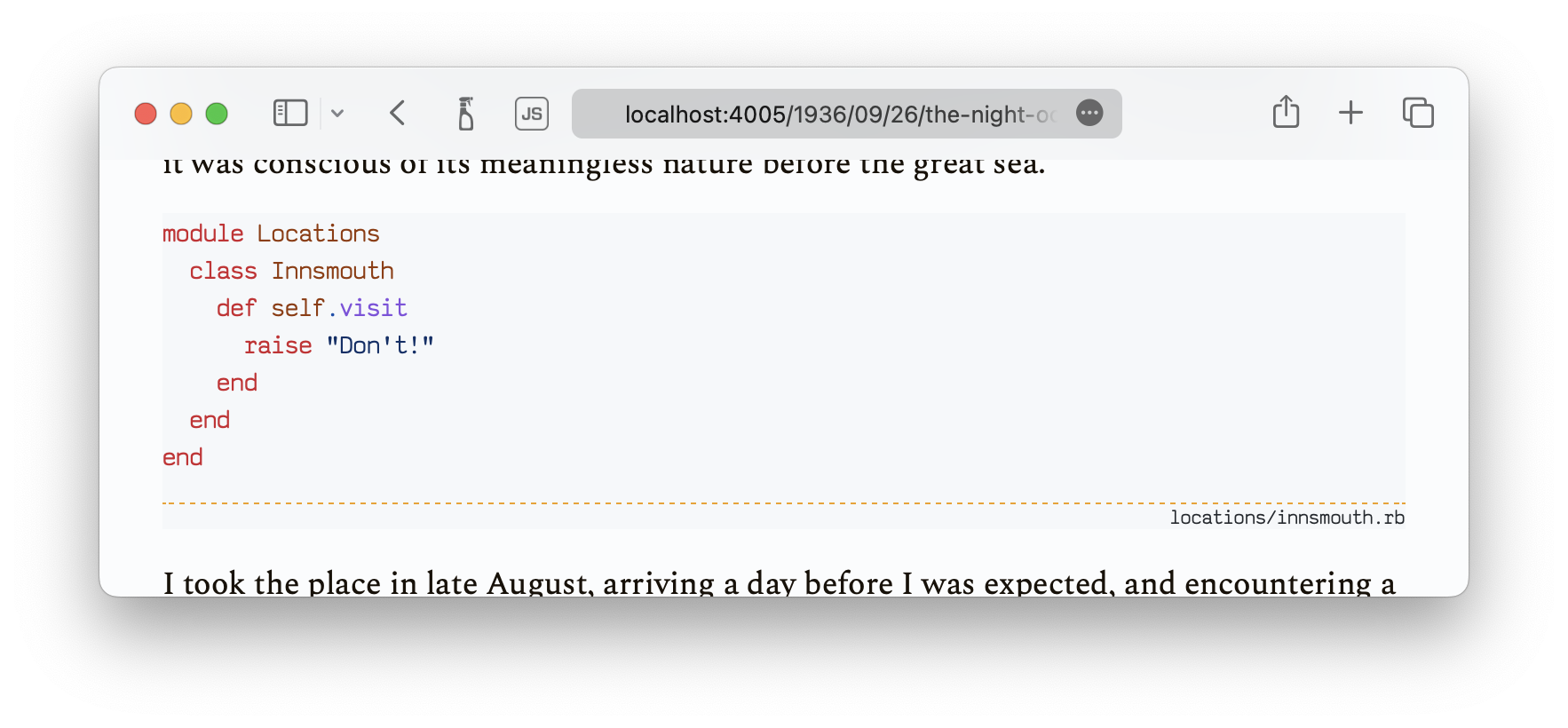

We experienced developers know better than to rush into a coding project without making sure that it has a valid goal,

and that this goal can only be reached by coding (more on that later). So, before anything, I used Safari’s web inspector to

try out the HTML above, ensuring that it would be valid, and that it would look good with some CSS. I was pleased with

the results:

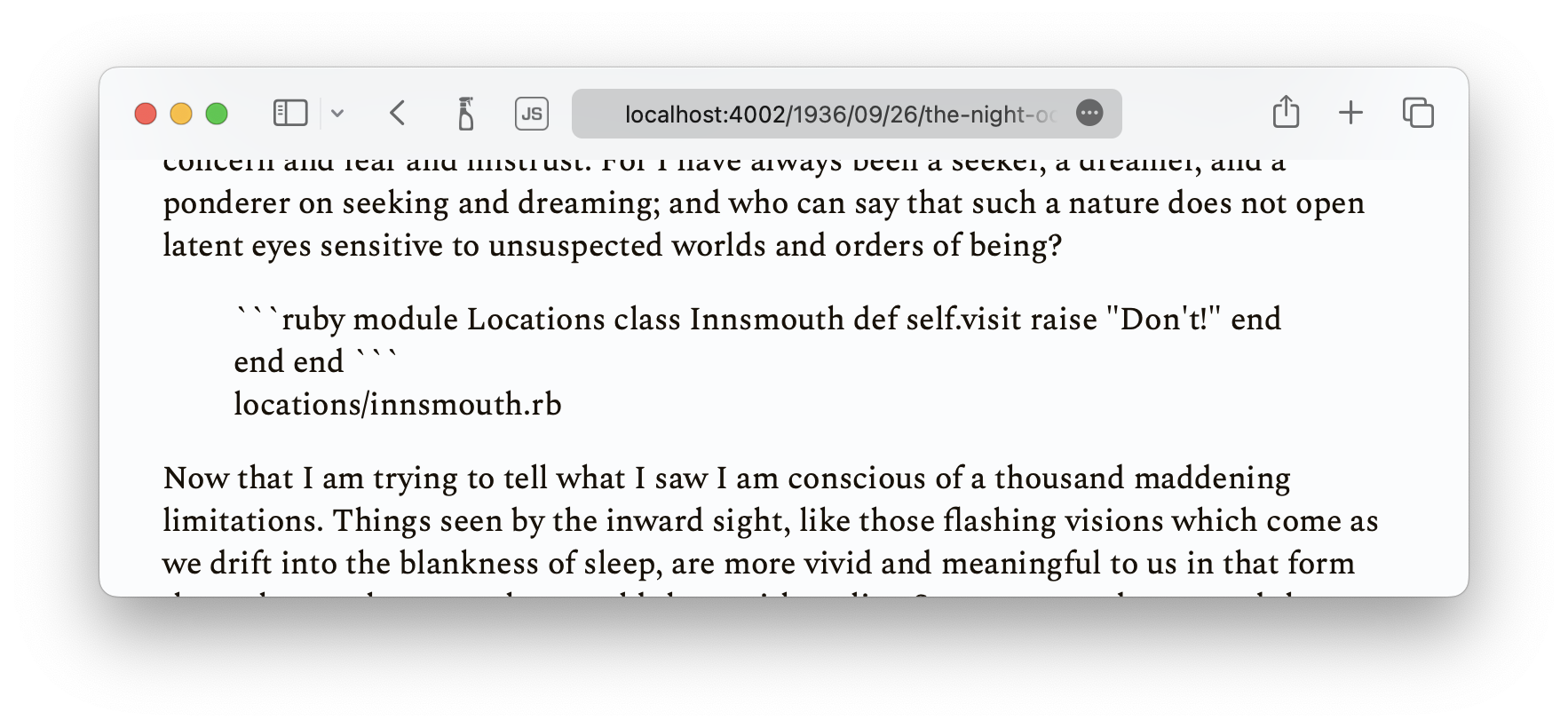

Next, not being a n00b, I made sure the markup I had set upon could not be obtained by simply adding the extra HTML tags to the Markdown content. Unfortunately, the Markdown specification is quite clear:

Note that Markdown formatting syntax is not processed within block-level HTML tags. E.g., you can’t use Markdown-style emphasis inside an HTML block.

To be sure, I tried it anyway:

<figure>

```ruby

module Locations

class Innsmouth

def self.visit

raise "Don't!"

end

end

end

```

<figcaption>locations/innsmouth.rb</figcaption>

</figure>

And indeed, the resulting HTML was not what I wanted (and rendered poorly):

Confident that <figure>‘s and <figcaption>‘s would indeed look good, but could not be generated without some

tinkering, I set sails to the high seas of Jekyll plugins, Markdown converters, and syntax highlighters.

Syntax highlighting for code blocks in Jekyll

The world of programming had long been my refuge from the terrors that lurked within the shadows. But as I delved deeper into the secrets of my static site generator, I realized that the very laws of OOP were nothing but a fragile veil, concealing horrors beyond human comprehension.

Having nitpicked on it recently, I knew that Rouge is what Jekyll uses to render syntax-highlighted code snippets. So I dived straight into its source and quickly found out that, in Rouge, the rendering is handled by formatters. Creating a custom formatter seemed easy enough, but I had to make it available to Jekyll, which meant pluging it to the inner workings of Jekyll, by configuration if possible, by hack otherwise.

Out of the box, Jekyll has two ways to render a code block with syntax highlighting, both ending up calling up on Rouge.

The first one is through a Jekyll-specific Liquid tag.

With this approach, Jekyll delegates to Rouge

(that is, if you’ve kept the default configuration),

using the either the Rouge::Formatters::HTML or Rouge::Formatters::HTMLTable formatters. Unfortunately, both classes

are hardcoded in Jekyll; however, I did not really care about this approach, because I don’t use Liquid in my Markdown posts.

(Among other reasons, I love Markdown for its portability; mixing a templating language to Markdown documents makes them

dependent on yet another processor.)

Instead, for code blocks I use the aforementioned fenced code blocks. In this case, the syntax higlighting is not handled by the Liquid converter, but by the Markdown converter. By default it is Kramdown, which happens to also delegates to Rouge for the syntax highlighting. (But note that, like Jekyll, Kramdown allows the swapping of the syntax highlighter for another.)

Kramdown wraps Rouge in its Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter::Rouge module. Here,

the default formatter is Rouge::Formatters::HTMLLegacy, but it too can be swapped for something else, as long as

the class or the name of this “something else” is passed as a converter option. This is in fact

pretty well documented, but of course I went through

the code before RTFMing, because why think when you can act?

So, after some partially needless code spelunking, I figured out that I could write a custom formatter for Rouge, and tell Kramdown to use it, so that Jekyll’s conversion from Markdown would generate the HTML I was looking for. The only missing ring in this chain of delegations was configuring Kramdown, but Jekyll makes this rather trivial.

The dive starts

With trepidation, I began my experiments, seeking to unlock the mysteries of this nerdy CMS and uncover the dark truths that lay hidden within

To put this plan to the test, I started with a dummy formatter:

require "rouge"

module Rouge

module Formatters

class NamelessCodex < HTML

def stream(tokens, &block)

puts "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn."

super

end

end

end

end

I then adjusted the configuration so that this dummy formatter would be used:

kramdown:

syntax_highlighter_opts:

formatter: NamelessCodex

And, sure enough, everything seemed to work fine:

𝄢 jekyll build -q

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Gaining confidence, I went to add extra markup to the formatted output – and then realized that I hadn’t thought about how to pass the caption to the formatter.

Well, it’s not entirely true. From a writer’s perspective, I had decided to use what GitHub calls

the info string – the part after the triple backtick

where the language is specified. I had seen it being used to pass extra options to some Rouge lexers

such as the console lexer.

My plan was to use the same trick, with a caption option:

```ruby?caption=locations/innsmouth.rb

module Locations

# …

end

```

However, only then did I realise that the info string was indeed passed to the lexers, but not to the renderer! And yet, the base class for formatters does accept options:

module Rouge

class Formatter

def initiatize(opts={})

# pass

end

end

end

And, indeed, Kramdown does pass options to the formatter, but unfortunately, they don’t include the target language, as I gathered by the arguments in this method:

module Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter

module Rouge

def self.call(converter, text, lang, type, call_opts)

opts = options(converter, type)

# …

formatter = formatter_class(opts).new(opts)

end

end

end

As you can see, the opts object is derived from the converter and type arguments, but not lang.

Through deeper explorations of Kramdown’s code, I understood what the converter, type, and

other arguments passed to .call were, and confirmed my suspicions: the info string was indeed

fully available as the lang argument – but had to be passed along the other options to

the formatter. Which meant using a custom Kramdown syntax highlighter, on top of a custom Rouge

formatter.

Going further down, one layer at a time

Despite the warnings of my runtime, I pressed on, driven by a maddening curiosity to control what lay beyond the threshold of Markdown parsing.

Like with the Rouge formatter, I wanted to start with a dummy syntax highlighter, which would basically do everything the basic highlighter does. Unfortunately, Kramdown highlighters are modules, not classes, so they cannot be inherited from, but I could still limit my own module to the bare minimum.

require "kramdown/converter/syntax_highlighter/rouge"

module RougeOutOfSpace

def self.call(...)

puts "Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!"

Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter::Rouge.call(...)

end

end

Before I could try this out, though, I had to tell Jekyll to tell Kramdown to use this syntax highlighter instead of Rouge (or rather, instead of Kramdown’s wrapper around Rouge…) Unfortunately, even though Kramdown does have a configuration option to swap the syntax highlighter, it wasn’t enough to simply set it:

kramdown:

syntax_highligher: RougeOutOfSpace

syntax_highlighter_opts:

formatter: NamelessCodex

That is because, unlike for the Rouge formatter, Kramdown doesn’t look for the relevant object

by searching for a constant within a given module (for example, Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter).

Instead, it keeps its own registry of “configurable stuff”, including a list of syntax highlighters, and “new

stuff”” has to be added to this registry to be available later on. Understanding all this took me some time and

meanderings in the seaweeds of Kramdown’s metaprogramming, but I eventually came up with something that worked:

require "kramdown/converter/syntax_highlighter/rouge"

module RougeOutOfSpace

def self.call(...)

puts "Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn."

Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter::Rouge.call(...)

end

end

Kramdown::Converter.add_syntax_highlighter :rouge_out_of_space, RougeOutOfSpace

kramdown:

syntax_highligher: rouge_out_of_space

syntax_highlighter_opts:

formatter: NamelessCodex

𝄢 jekyll build -q

Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Iä! Iä! Cthulhu fhtagn!

Ph'nglui mglw'nafh Cthulhu R'lyeh wgah-nagl fhtagn.

Finally, I could implement a syntax highlighter that would extract the caption from the info string, and pass it to the formatter. Which, for the former, unfortunately meant some copy-pasting from the original module – but I was still pleased with the end result.

class NamelessCodex < HTML

def initialize(opts = {})

@caption = opts[:caption]

end

def stream(tokens, &block)

yield "<figure>"

super

yield "<figcaption>#{escape_special_html_chars @caption}</figcaption>" if @caption

yield "</figure>"

end

require "kramdown/converter/syntax_highlighter/rouge"

module RougeOutOfSpace

def self.call(converter, text, lang, type, call_opts)

opts = Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter::Rouge.options(converter, type)

# extracting the :caption option from the "lang" (actually the fence string) for the formatter

opts[:caption] = /caption=([^&]*)/.match(lang) { |md| md.captures.first }

call_opts[:default_lang] = opts[:default_lang]

return nil unless lang || opts[:default_lang] || opts[:guess_lang]

lexer = ::Rouge::Lexer.find_fancy(lang || opts[:default_lang], text)

return nil if opts[:disable] || !lexer || (lexer.tag == "plaintext" && !opts[:guess_lang])

opts[:css_class] ||= 'highlight' # For backward compatibility when using Rouge 2.0

formatter = Kramdown::Converter::SyntaxHighlighter::Rouge.formatter_class(opts).new(opts)

formatter.format(lexer.lex(text))

end

end

Now everything was in place – after hours of sorting through arcane code, I had a custom Rouge formatter, used by

a custom Kramdown syntax highlighter, both made available as Jekyll plugins. I only had to check the results:

Dispair, madness and losing one’s way

As I gazed upon the accursed web page, its blasphemously unformatted code sections seemed to writhe and twist before my eyes, revealing truths that my mortal mind could never comprehend, and in that moment, my sanity was forever lost to the abyss…

It didn’t work! Though the caption was there, the code was not highlighted – it wasn’t even formatted. Looking at the

source, I realized that some elements, most significantly the <pre> and <code>, were missing:

<div class="language-ruby highlighter-rouge_out_of_space">

<figure>

<span class="k">module</span>

<span class="nn">Locations</span>

<span class="k">class</span>

<span class="nc">Innsmouth</span>

<span class="k">def</span>

<span class="nc">self</span>

<span class="o">.</span>

<span class="nf">visit</span>

<span class="k">raise</span>

<span class="s2">"Don't!"</span>

<span class="k">end</span>

<span class="k">end</span>

<span class="k">end</span>

<figcaption>locations/innsmouth.rb</figcaption>

</figure>

</div>

And this is where, I confess, I lost my way. Re-reading Rouge’s source code, and especially the Formatters::HTML class

which as far as I understood was the formatter normally used by Kramdown, and from which my custom formatter inherited, I

saw not mention of these missing <pre> and <span> elements. So I came to the conclusion that these were actually

added by the Kramdown converter, one level of delegation beyond (or is it before?) the syntax highlighter! This

meant that I also had to write a custom HTML converter for Kramdown; one which would correctly wrap the syntax highligher code

blocks in <pre> and <code> elements.

To understand how to write such a converter, I dove deeper into Kramdown – and lost even more time and sanity

figuring out how the Markdown-to-HTML works there, and especially the treatment of code blocks. It was a

tortuous expedition, in part because Kramdown is not really meant for converting Markdown – it’s originally built to

convert a Markdown-inspired format (also called Kramdown!), which uses a different marker for fenced code blocks (~~~).

But Jekyll adds a plug-in to Kramdown, so that it understands another Markdown variant, GFM, which is where the

fenced-code-blocks-with-backticks come from.

At that point, I stopped and reconsidered my plan. From a custom Rouge formatter, I had come to coding said formatter, plus a Kramdown syntax highlighter, had read through more metaprogramming-rich code that I could stay sane with, and was about to code a third custom component, this time a custom GFM-to-HTML converter for Kramdown. Was it really necessary? Worth it?

Back on the bridge

As I delved deeper into the ancient tome, my eyes fell upon a cursed passage, that would lead me to a fate worse than death

In my initial preparations, I had tried simply mixing HTML code with Markdown (or, rather, GFM) markup, to no avail. But

could it still be done? A bit of research on dubious websites led me to the conclusion that, yes, such mixing was allowed

in CommonMark – yet another Markdown variant, upon which GFM is based. But to use CommonMark, I would have to replace

Kramdown with another processor, jekyll-commonmark.

Once again, this is documented and easy to do.

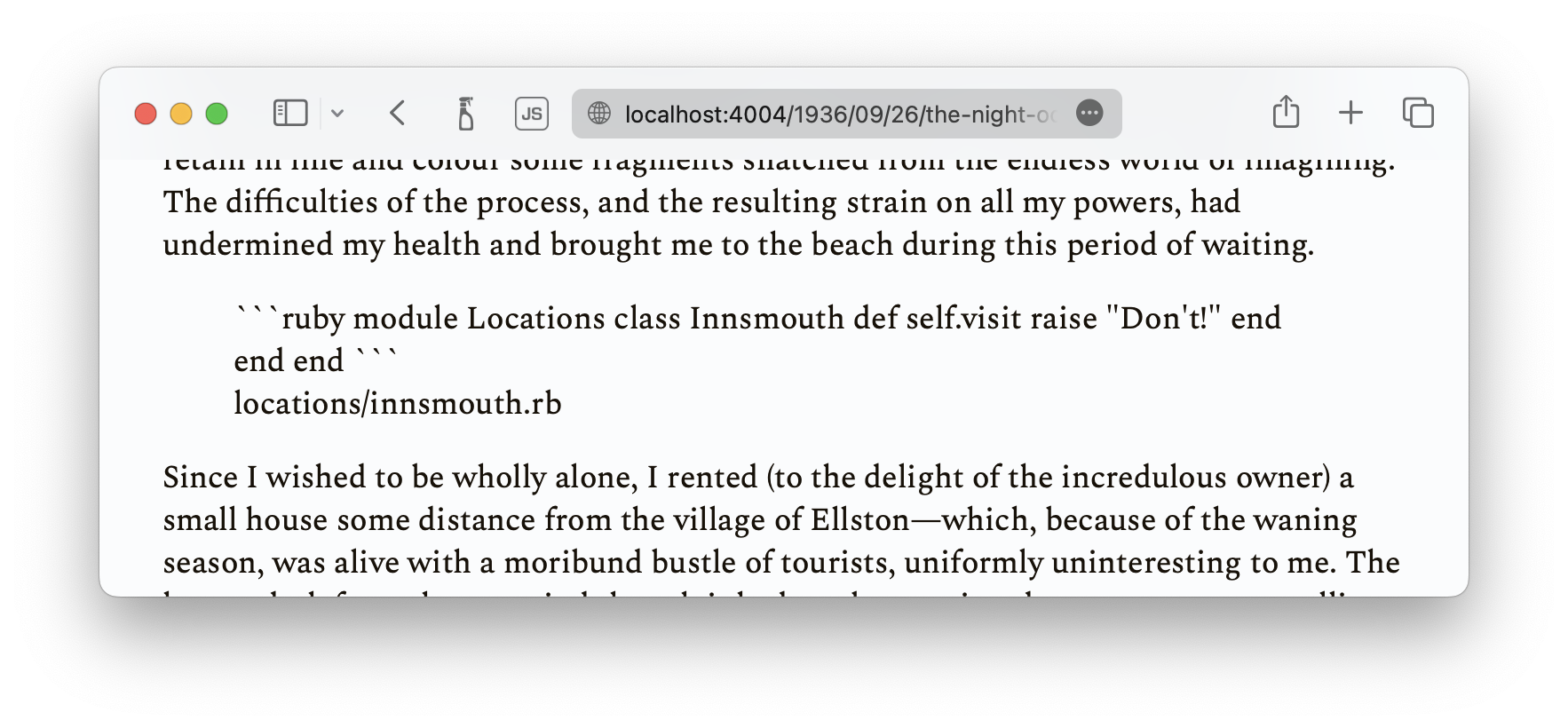

Unfortunately, a first try with my sample didn’t seem to work:

I understood why after reading closely the CommonMark spec:

- Start condition: line begins [with] the string [<figure].

- End condition: line is followed by a blank line.

For my HTML/CommonMark mix to be properly converted to HTML, I needed to add a blank line at the end of the HTML part, like so:

<figure>

```ruby

module Locations

…

end

```

<figcaption>locations/innsmouth.rb</figcaption>

</figure>

The call of the depths

Blinded by my own hubris, I ignored the signs of impending doom and continued my quest for forbidden rendering.

This simple change was enough to make the content generation go perfectly, but it left me unsatisfied. I didn’t like this extra blank line that I was forced to add - it was unpleasant to my reddened but still delicate eye. And I resented CommonMark for making this requirement so difficult to figure out. So, in my folly, I decided to go back to writing a custom component that would leverage my previous work on Rouge and Kramdown. This time, it would have to be a renderer, in the jargon of jekyll-commonmark.

So I dove once again in a new code base and a new plugin, reading through the HTML renderer to better build upon it. I put my sanity at risk by trying to come up with clever regexes, only to realize that I would also need to build a custom converter, which would make use of my custom renderer. I felt caught in a time loop. Still, I persevered and came up with something that worked:

require "commonmarker"

class Jekyll::Converters::Markdown::Necronomicon < Jekyll::Converters::Markdown::CommonMark

def convert(content)

CursedHtmlRenderer.new(options: @render_options, extensions: @extensions).render(

CommonMarker.render_doc(content, @parse_options, @extensions)

)

end

class CursedHtmlRenderer < Jekyll::Converters::Markdown::CommonMark::HtmlRenderer

def code_block(node)

block do

lang, *options = node.fence_info.scan(/(?:(\A\w+)\??)|(?:(\w+)=([^&]+)&?)/).flatten.compact

options = Hash[*options]

out('<div class="')

out("language-", lang, " ") if lang

out('highlighter-rouge"><div class="highlight">')

out("<figure>")

out("<pre", sourcepos(node), ' class="highlight"')

if option_enabled?(:GITHUB_PRE_LANG)

out_data_attr(lang)

out("><code>")

else

out("><code")

out_data_attr(lang)

out(">")

end

out(render_with_rouge(node.string_content, lang))

out("</code></pre>")

out("<figcaption>#{options['caption']}</figcaption>") if options.has_key? "caption"

out("</figure>")

out("</div></div>")

end

end

end

end

The custom converter (Necronomicon) is only there to ensure that the custom renderer (Necronomicon::CursedHtmlRenderer)

is used; it has to be placed in the Jekyll::Converters::Markdown namespace because

that is where Jekyll looks for it

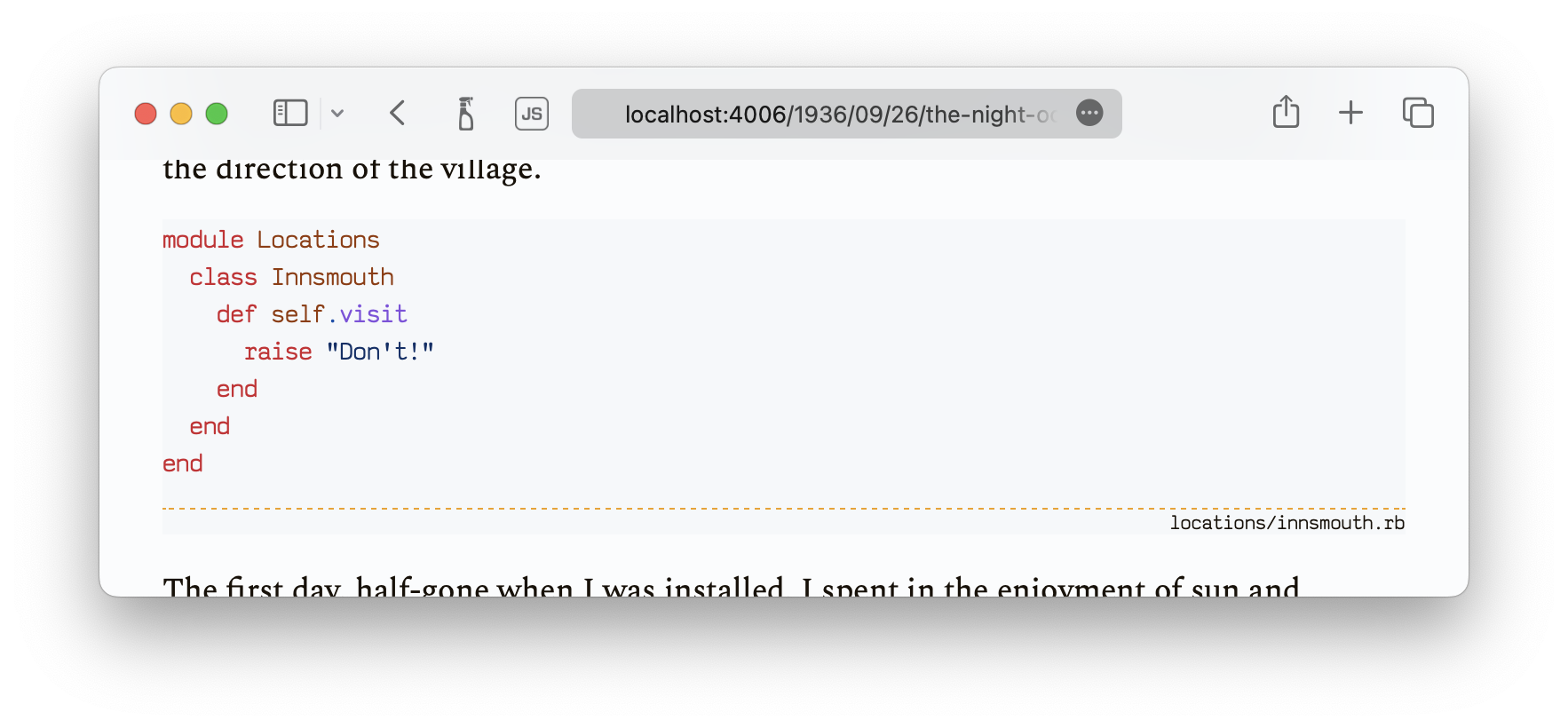

And so, in exchange for a little more of my sanity, I now had a second way to render code blocks in an elegant and

semantically correct fashion:

However, the cosmic forces that govern us are nothing but cruel masters, and on their whim I decided to look again, more closely, at Kramdown’s documentation.

Back home, forever changed

As I gazed upon the tangled mess of code before me, I realized with a sinking feeling that I had come full circle, my cursed journey through the labyrinthine world of cyclopean programming having led me back to the very beginning.

Here is what the Kramdown (the format, not the gem) documentation says about HTML blocks:

Difference to Standard Markdown […] the original syntax does not allow you to use Markdown syntax in HTML blocks which is allowed with kramdown

So, just like CommonMark, Kramdown allows the mixing of raw HTML and Markdown. But did my initial test fail? Is a blank line necessary in Kramdow, too? I found the answer further down the documentation:

If an HTML tag has an attribute markdown=”1”, then the default mechanism for parsing syntax in this tag is used.

I wasn’t sure what “the default mechanism” was, but I gave it a try:

<figure markdown="1">

```ruby

module Locations

class Innsmouth

def self.visit

raise "Don't!"

end

end

end

```

<figcaption>locations/innsmouth.rb</figcaption>

</figure>

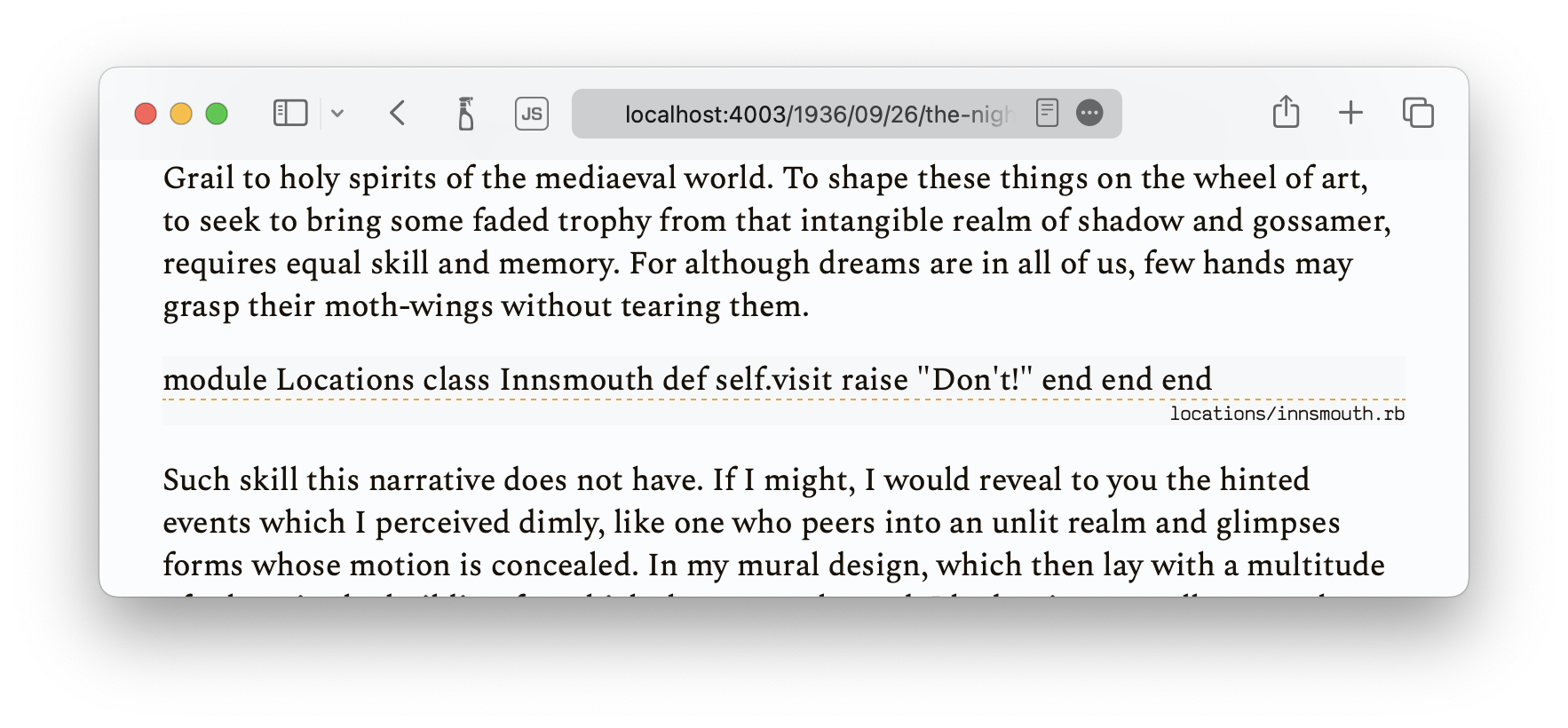

And, to my relief and despair, it worked perfectly:

Now I could get rid of all my work – the custom Rouge formatter, Kramdown syntax highlighter, and jekyll-commonmark converter and renderer. All these were useless, since what I wanted had been available from the start – all was needed was an extra HTML attribute. As the documentation explained.

Unspeakable learnings

Through my journey into the abyss of four different gems, I learned that the arcane secrets of the universe are not meant for mortal minds, and that the price of forbidden knowledge is a terrible and eternal damnation, not to mention an ironic waste of time.

This “nice little coding project” turned out to be more eventful than I was expecting – but I did gain some rolls for skill increases in exchange for my SAN points.

First, I came to realize how much of a mess the Markdown situation is. I knew about variants like Github Flavored Markdown, CommonMark and a few others such as MultiMarkDown, but I naively thought that GFM had become a de-facto standard, of which CommonMark was only the official spec, like ECMAScript is to JavaScript (it is not). More importantly, I underestimated how much they differ, from the original Markdown and from one another. This led me to wrong assumptions when I went looking for a codeless way to reach my goal.

Second, I got to know the inner workings of Jekyll. I may disagree with some of its design choices, like using Liquid or the way collections work, but going through the code was a nice experience. Everything is well-architectured, and easy to understand.

On the contrary, I wasn’t conviced by Kramdown, the gem. It is a big piece of software, it does a lot of things, and it does them well. And I appreciate its overall architecture and care for extensibility (like Jekyll, and like Rouge for that matter). However, I found the code itself tortuous, overly generous in metaprogramming and Ruby acrobatics, while the test suite documents little (it’s mostly a suite of abstracted integration tests.) The code reads like the solo project of a clever programmer who’s having fun pushing himself; I would have enjoyed writing it, but I disliked reading it. Somehow, it fits with Kramdown, the format. It is very complete, well thought-out, and it answers actual needs, but I simply don’t enjoy it. It is too close to an actual templating language – I was half-expecting to see syntax elements for loops and conditionals. (To be honest, the same could be said of CommonMark.)

However, I have to admit that, as overly rich as Kramdown is, it is well documented. And this is probably the main lesson of this adventure: read the fucking manual. All the pieces I needed were documented: the Jekyll docs says that Kramdown is used (with a GFM variant), and the Kramdoc documentation says how HTML blocks and Markdown can be mixed. Yes, everything is not super clear, but still: I could have saved myself the whole trip down the code of 4 different gems if I had taken the time to read the docs first.

But, on the other hand, it was a funny trip, and I brought back interesting souvenirs.

Artefacts on the library’s shelves

The eldritch relics I brought back from my journey now sit locked away, their very presence a reminder of the horrors that lie beyond the veil of our reality.

I now have 4 different ways to wrap my code samples in a <figure> element, with an associated <figcaption>.

- Mixing HTML and Markdown, following Kramdown’s syntax (a

markdownattribute added to the wrapping HTML element). - Mixing HTML and Markdown, following CommonMark’s syntax (blank lines after the HTML elements).

- Using the info string, thanks to a custom Rouge formatter and a custom Kramdown syntax highlighter. (After a good night sleep, I understood my mistake and fixed this first attempt.)

- Using the info string, thanks to a custom Markdown processor (derived from jekyll-commonmark).

For the time being, I’ve decided to go with the first one, as I’ve narrated above. However, I’m not entirely happy with this solution. I like to stick to the defaults as much as possible, whether it’s for my computer setup, my test runner in Ruby, or my Markdown texts. I prefer to use the original Markdown as much as I can; I can go with GFM because it’s so ubiquituous in the programming world (and I like most of its additions to Markdown, to be honest). So using the info string would make sense, but it confuses my text editor – so even if the final result looks fine, using this syntax is unconfortable. On the contrary, the extra HTML markup doesn’t look too bad, especially without the extra blank line that CommonMark requires.

So that’s my trade-off for now: going with Kramdown’s syntax instead of the simplest Markdown, in order to have the benefits of a good rendering and a good writing experience. But the more I think about it, the more I’d like try moving the syntax-highlighting to the client side, so that I could get rid of the code fences altogether:

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet.

<figure><pre><code lang="ruby">

class Consectetur

def adipisicing(elit)

end

end

<figcaption>sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt</figcaption>

</code></pre></figure>

I’m still on the (code) fence as to wether it makes the text less legible or not. We’ll see.